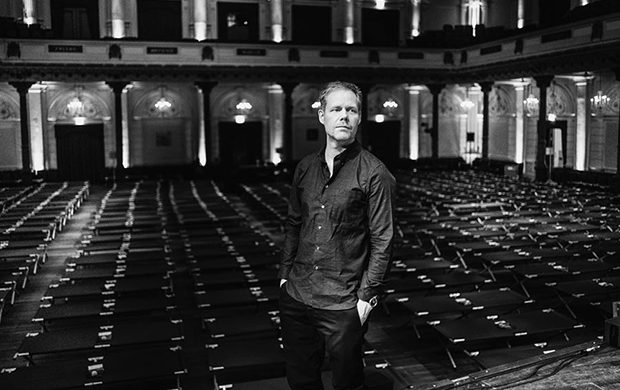

Olivia Allwood-Mollon interviews world-renowned composer Max Richter; they talk neuroscience, childhood, escapism, isolation, and this weekend’s global broadcast of SLEEP, his 8-hour epic “lullaby for a frenetic world”

Where are you currently based in the world and why?

Oxfordshire – middle of nowhere – it’s a good place to be right now, and my home base.

Your 8 hour piece SLEEP is about putting things on pause, and is now more apt than ever – has your perspective on it changed at all in the context of lockdown?

Yes, it’s interesting, isn’t it? One of the starting points was really my sense that our bigger selves were being crowded out by data saturation and all the digital virtualising of our lives, and that we were sort of missing some of the really human fundamentals. The idea behind SLEEP really was to make this big pause that would allow us to reconnect to these things and reflect on them. But of course, now we’re in this situation where all we’ve got is time to reflect on things.

None the less, this time isn’t neutral, it’s been forced upon us and is filled with anxiety and trouble and suffering – I think creative work can kind of speak to this moment. When I wake up the first thing I do is put the radio on and listen to music in the kitchen in the background all day long. We use movies and paintings and novels to take us out of our ordinary reality, and I think that’s something we could all do with right now.

And when did the idea for a global Easter broadcast come about?

Everything is pretty last minute at the moment really, none of us has ever been in a position like this before. The BBC came up with the idea as part of their Culture in Quarantine series and it really grew from there to being broadcast with other partner stations across the world in Europe and the US.

You consulted a neuroscientist while composing SLEEP, what input did they have?

I spoke to novelist, neuroscientist and Stanford professor, David Eagleman – I’d previously done an opera based on one of his books and had instincts about the kind of music that would be appropriate to be slept through, but wanted to check it out with someone who understood the science. We talked a lot about repetition and structural ideas. Frequency spectrum is very important acoustically – we removed all high frequencies from almost the entire piece, mirroring the frequencies heard by an unborn baby. I introduced higher frequencies in the final hour to gradually wake the listener up, in a similar way to a sunrise.

What do you think music might sound like in 500 years?

That’s a really interesting idea! I don’t know, we’re very used to the idea of thinking in terms of progress – our imaginations are hijacked by product research and development cycles, and corporations – the next tv, the next car, the next whatever it is, and we think of the future in these terms. But ultimately our bodies don’t know it’s the C21st and they haven’t changed in 100,000 years – creativity and culture speak to really fundamental human things.

Technology might change, but I suspect we’ll still have love songs and music for dancing. The things that make us want to tell stories are fundamentally the same, falling in love, breaking up, people being born and dying – all those big things.

How has the lockdown affected you creatively – do you feel able to compose when solitude is mandatory?

Well, in a way it suits me rather well! I’m slightly reclusive anyway and my work is very much me sitting in a room scribbling on a piece of paper, so it’s had basically no impact. I feel incredibly lucky in that sense as almost everyone’s life’s been completely turned upside down.

Your career as a composer spans everything from film and TV scores to reworking Vivaldi, to more experimental pieces – do you have a favourite type of project?

I’m really fortunate in that I get to do things I love doing – which is my criteria really for taking on projects. The records and solo projects are the heart of my work as I have complete autonomy, but I do love the collaborative things, tv, film ballet, whatever it is – I love that collective puzzle solving aspect to it. I think if I didn’t do other things and collaborate I’d probably go slightly mad.

What music do you listen to when you need uplifting and inspiring?

I listen to a lot of different things, It depends what kind of uplifting – I listen to a lot of classical music – Bach is my go to for pretty much any occasion. I love Schubert, I love Renaissance music, and I also like noisy electronic music, and one of the most uplifting things is some of the early Dylan stuff, which is not commonly produced but quite shouty, which I really enjoy!

What are you working on now?

Right before lockdown happened, I premiered a new piece, Voices, at the Barbican, which we managed to record in the last few days that we were still allowed out. It’s based on the UN Declaration of Human Rights.

Could you give us a brief overview of your daily routine, if you have one?

I get up fairly early and do all the various school runs and things like that, then go to the studio and pick up wherever I left off the night before, I just keep going until lunchtime, where I’ll make some lunch, then the afternoons tend to be busy with admin and ordinary life things. But my routine is pretty much just writing and composing!

What do you do when you feel trapped or stifled, as many of us are right now?

I guess I go back to the kinds of books, movies and pieces of music that open up another world, an imaginary world, and that’s what’s so beautiful about creativity – every novel every film, every piece of music is an alternative universe that you can visit.

Do you think the way opera houses and orchestras are sharing their content online during lockdown will leave a legacy for the way classical music is consumed?

It’s very interesting and I think it’s wonderful the way people are finding ways to keep music playing, and hopefully it will allow people who would never go to an opera house or classical concert to experience it.

When did you first know you’d become a composer?

I always had music going round in my head from a very young age – a combination of things I’d heard and things I’d made up. I just treated music in the same way I treated my other toys, things like building blocks – I thought that was a totally normal thing. I just played with music in my head, all the time, and didn’t realise this was unusual.

What role do you think the arts play in unifying and inspiring people in times of global crisis?

I think they allow us to connect in a different way. They allow us to have common and shared experiences, they foster a sense of community and also promote a sense of possibility, possibility beyond the here and now, of something bigger, and that’s what’s so important about creativity and the arts, now in lockdown, but also all the time, especially in schools, music education and arts education, not just now, but as part of ordinary life.

Which composers have inspired you the most over the years?

I listen to different music for different reasons, Renaissance music is really fundamental because you get this beautiful combination of incredibly well-made, clever musical structures and yet a beautiful, direct emotionality, which I love about it. And obviously Bach – I think for every musician and composer, Bach is the beginning of everything. And a lot of C20th classical stuff too.

What is the trait you most admire in others?

I guess thoughtfulness.

And yourself?

I’m not sure I admire any traits about my self (laughs).

What are you most proud of and why?

I guess I’m most proud really of being able to spend time doing what I’m doing, which as I child I never believed I’d be able to, and to have a functioning family – I’ve been incredibly fortunate in my life to have supportive and wonderful people around me – and never assumed I’d have either of these things as a child.