Review - 1984

By Alexandra Bell

1 Sep 2016

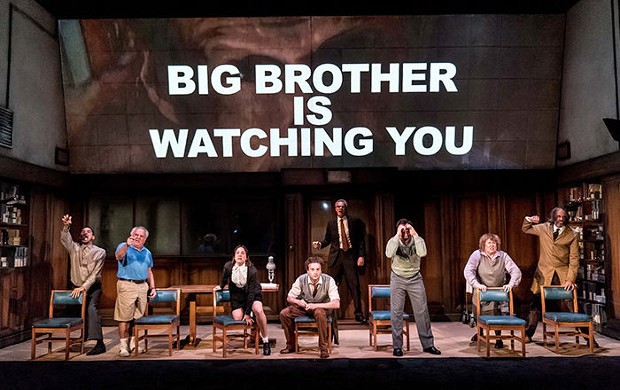

Lights flash, creating a strobe effect on stage; buzzers blare cacophonously, the protagonist freezes on the set as he is plunged into an alternate present, while a massive screen presents another window on the action of the play. This is all in the first few minutes—the Robert Icke/Duncan Macmillan production of 1984 at the Playhouse certainly can’t be accused of dragging its feet.

Thrown in at the deep end, we enter the world of Winston Smith as he starts his famous diary, a record of private thought that challenges the dystopian system he lives in by its very existence. Then we are thrown in again, as the scene changes to a seemingly post-dystopian book group discussing the diary and its mythic author, as Winston sits there in dazed shock, part of both worlds but at home in neither.

The book group draws upon Orwell’s Appendix to 1984, which, in scholarly fashion, implies that Oceania’s totalitarian society collapsed at some point after the events of the book proper due to the impossible attempt to constrict language; here Icke and Macmillan have used this detail to create an alternate 21st century setting that follows 1984′s timeline, but seems otherwise not dissimilar to our own.

These dizzying switches between times and settings, heralded by sensory-overloading light and noise, are a central feature of the staging. At first they feel overwhelming and slightly confusing, but this is part of the point—they signify not only a temporal disturbance, but a mental one, referencing Winston’s future (or past, depending which era you inhabit) sojourn in the Ministry of Love as well.

They throw the action on stage into doubt, as it skitters between an uncertain far future (real? Imagined?) and an already-written unfolding present, both happening before us and being recalled by the disintegrating, assaulted mind of the Winston who seems the most actively present throughout, as he is interviewed by O’Brien in Room 101—even if he is only physically on stage at the end. The occasional reverberating echoes of O’Brien’s interrogation as the story progresses underline this feeling of the inevitability of our protagonist’s fate, foreshadowing the ever-looming silhouette of the Ministry of Love. We live the tale of Winston’s rebellion through his own unreliable senses and memories.

This arrangement is not the only effective aspect; the ever-present telescreen spanning the stage offers ample opportunity for Icke and Macmillan to play with their material in new ways, from the live-screening of all that happens in the off-stage ‘secret’ room where Winston and Julia hold their dalliances—inviting the audience to be party to their recording and betrayal, Big Brother-style—to renderings of state-sponsored video clips and ‘news’ segments. The breathtakingly vicious Two Minutes’ Hate is particularly memorable, horrifying yet (very) darkly comic in the mirror it holds up to our society.

There are many bridges in the production to current events and political debate, as you would expect; it is hardly news that the content of 1984 has been hailed as prophetic. These links are most effective, though, when allowed to speak largely for themselves, such as the description of Winston’s job deleting unpersons from all records or the backwards editing of history, which is unnervingly easy to take in your stride, especially plausible in this age of ever-increasing digitisation.

I balked, though, at the final scene, as a member of the futuristic book group says darkly, in response to the assertion that the Big Brother state of Winston’s diary no longer exists, that maybe it is simply more subtle, controlling us from the shadows—we get it, the parallel to today’s WikiLeaking, whistleblowing world. The clear brotherhood of their and our 21st centuries was enough on its own without having to have spell it out quite so painstakingly.

The compact, talented cast work well to emphasise the disorientation of the staging, cast members popping up again as different characters in different eras, often containing deja-vu echoes of their alternate roles. Angus Wright is a pleasure to watch as ever, pulsating with ominous, thoughtful deliberation as O’Brien, and Catrin Stewart’s Julia bubbles with unpredictability and impulsive disobedience, in contrast to Andrew Gower’s uncertain, frustrated Winston.

Sometimes the latter’s almost bumbling quality throws off one’s belief in him as the revolutionary protagonist of the piece, more so given the partial removal of his agency to future memories and rereadings, but this rendering works in other ways. Winston was never a great leader of men, a rallier of the masses, but a quiet man who feels an irresistible welling up of rebellious discontent, someone who intellectualises his surging disgust with the system even as he feels it. He sees even his personal revolution through the lens of his memories and his writing rather than with the immediacy of feeling of the Julias of the world; how apt, then, that we too view it through the various lenses presented by the production.

In short: while there are small decisions that grate, it is no doublethink to say that 1984 is bound to intrigue. From the contemporary parallels played up in both the language and the staging, to the multisensory stimulation and complex unfolding of the performance, it deserves a viewing before the run finishes at the end of October.